The Urban Planning Challenges of Language in India

By Sonia Suresh

My favorite phrase in Hindi is Main ghum gahee hoo. Aside from being to fun to say, it comes in handy because it means “I’m lost.” Of course, getting lost — whether because of culture or geography — is all in the adventure of being in a new country.

However I came into this internship rather arrogantly assuming I would be sailing through a summer in Mumbai. I spent many childhood summers in my family’s hometown of Bangalore and I traveled throughout the country for several months last year. I figured accumulated time and the ability to count to 10 in Hindi would make up for not actually speaking the language. So far, this summer has been a much deeper observation than my previous visits into the ways, language and culture in India are entwined in everyday life and urban planning.

I’m puzzling to many of the people I interact with on a daily basis, including my co-workers, cab drivers, fellow train riders. I look Indian but my blank face after confronted by a stream of Hindi and unawareness around certain customs and cultural norms are giveaways before I open my mouth and my American accent solidifies my foreignness. I often opt to stay silent because if I don’t say anything, I can hide behind my Indian features and pretend to know what’s going on.

My least favorite phrase? Main Hindi nahi janthi hoo or “I don’t speak Hindi.” These words are a sheepish confession, effectively ending the charade. I can pull off the infamous Indian head shake, so I often employ it and hope that I don’t agree to something I will regret. Some people are sympathetic to my ignorance. Others are not. Confusion turns into disdain, something I subject myself to as well. Why don’t you know how this works?

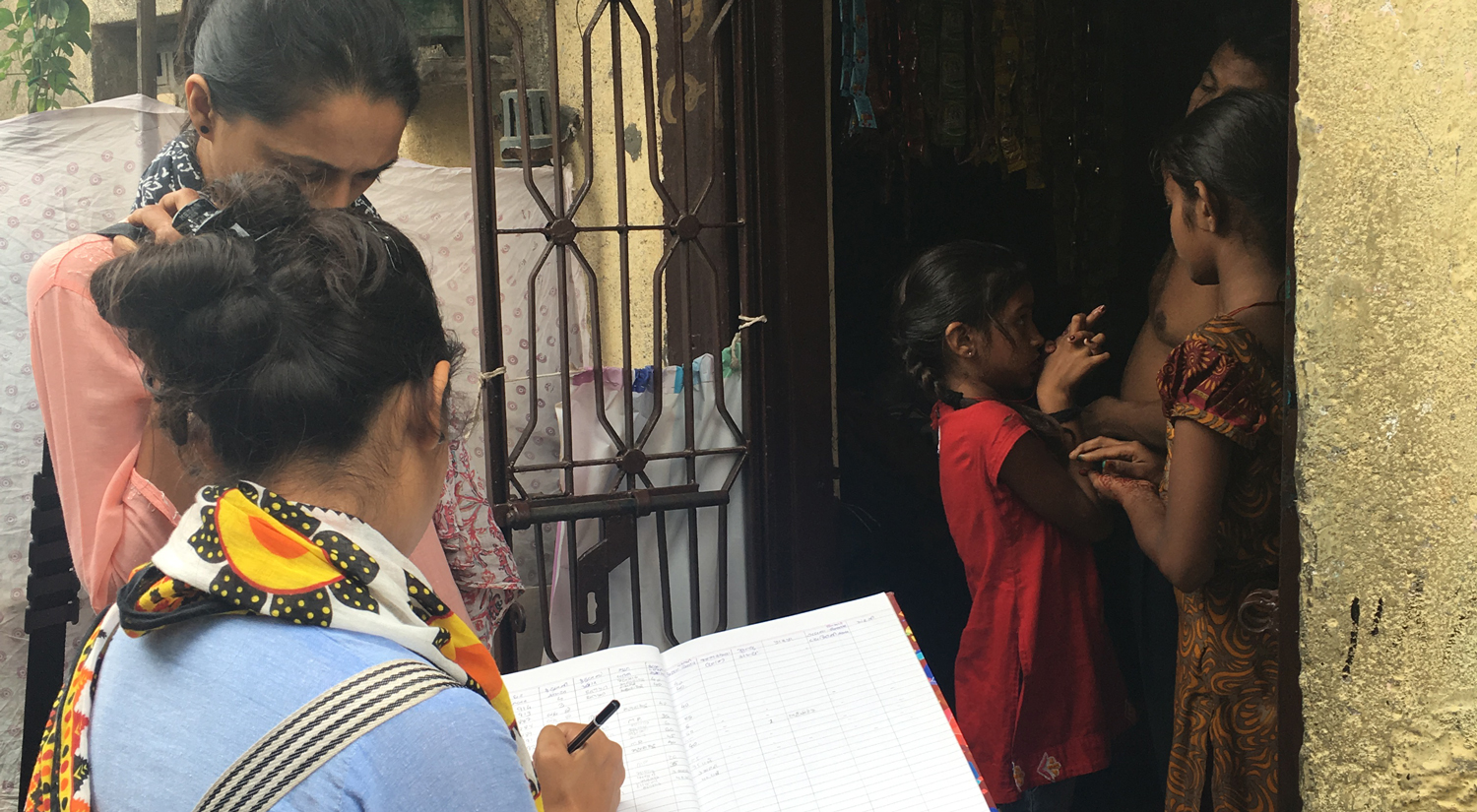

At work, language presents different kinds of challenges and interesting insights. My internship this summer is at the World Resources Institute working on a resilience indicator tool for slum communities. Work is primarily conducted in English but many conversations, especially when in the heat of important discussion or at the lunch table, flow into Hindi. To add to the mix, the communities we are surveying are in a city called Surat in Gujarat where the primary language is Gujarati. In my cloudy haze of perception of these three languages, I worry about what’s getting lost in translation with an American concern for efficiency that my colleagues don’t seem to share. Our community partner in Surat is the Urban Health and Climate Resilience Centre of Excellence (UHCRCE). When UCHRCE sent us their edits of our survey tool in Gujurathi, requiring a three-hour meeting to demystify, I lamented the several days worth of work we had put into refining the questions in English. Sure, this could have been a more streamlined process, but the point isn’t necessarily to be efficient in the way I’m used to thinking of it. We defer to the community and that takes time and patience.

The development of the survey has been a year-long process and included multiple rounds of extensive focus group discussions and will include more as we continue to refine the tool. Even then, it’s not enough. Over half the population of Surat is made up of migrants from other states. Although the focus group discussions were conducted in both Gujarati and Hindi, my colleagues regrettably felt a number of community members were not engaged as they did not speak either language. Here language barriers are taken very seriously because of the multitude of languages spoken. This is a stark contrast to my experiences working in planning in San Francisco, where translation was something we simply checked off the list when planning for a community meeting rather than being an integral part of the planning process.

The issues around language in India are complex though. There’s a strong sense of regional pride and identity in language, which has political implications. With a government that encourages nationalism and exclusionary policies, I wonder how the diversity of languages will fare in the future and urban planning’s role in this. My understanding of these issues is still relatively nascent, but it’s something I hope to understand further. This week we are heading to Surat to meet with UHCRE to discuss the scoring of the survey and next steps. I’m eager to see how we will approach the next round of focus group discussions and what other insights will come from our meeting and the rest of the summer.